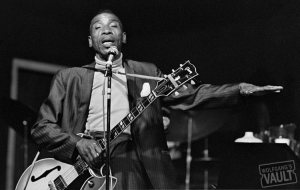

Crush Holloway

Almost 15 years ago, while I was a grad student at IU and (at the time) researching and writing about the blues – my absolute favorite type of tunes – I traversed northwest Mississippi and southeast Arkansas visiting the graves of five legendary bluesmen.

Those five were Elmore James (buried at Newport Missionary Baptist Church in Ebenezer, Miss.), Mississippi John Hurt (a family cemetery tucked away in his hometown of Avalon, which for all intents and purposes is a dead town now), Sonny Boy Williamson II (Whitfield Baptist Church, Tutwiler, Miss.), Albert King (Paradise Gardens Cemetery, Edmondson, Ark.) and Charley Patton (Holly Ridge Cemetery, Holly Ridge, Miss.).

While pursuing the ghosts of greats, I took notes and did interviews at every stop, with the intention of turning the experience into a book, a book chapter or a long essay.

It didn’t turn out that way, of course. The project fell by the wayside after I graduated from IU, consigned to the ever-growing dustbin of starry-eyed, abandoned and forgotten projects from the last 21 years of my life. (That list, naturally, includes probably half a dozen incomplete forays into literary journalism concerning various Negro Leagues topics, a fact that I might discuss in a later post.)

I did manage to turn my aborted travelogue into a presentation at the annual Delta Symposium at Arkansas State, but even that was somewhat pulled out of my arse – I essentially just winged it and depended on my immense personal charm and charisma to get me through.

I also wrote a really good article about the John Hurt leg of my trip for Blues Revue magazine, and I managed to crank out a personal essay/narrative about my time and investigations at Holly Ridge.

However, I’ve lost the text to that piece, as well as the entirety of my notes and files from the project, a situation is, to say the least, crushing and deflating. Perhaps all that stuff will turn up when I move next, but if not, it’s probably gone, lost into the vapors of my stunted career goals.

Why do I bring all this up? Because recently, I’ve been pondering the connection between music and segregation-era black baseball. Especially during the years before the integration of the national pastime, at a time when aspiring African-American hardballers simply couldn’t make ends meet as a full-time player, music could have been a secondary source of income for them.

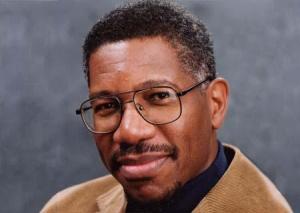

T-Bone Walker

Now, there’s no question that in the country’s urban areas where blues and R&B thrived – Kansas City, Chicago, New York, Memphis, Indianapolis, New Orleans – Negro Leaguers and black music stars of the day intermingled and developed lasting friendships and a sort of financial symbiosis.

After playing a game in one of those cities – and other burgs, like Newark, Pittsburgh and Detroit – Satch, Josh and other baseball stars hit the Crawford Grille or the Paseo Ballroom or the Apollo or the 708 Club to take in concerts by Duke Ellington, Count Basie, T-Bone Walker, Leroy Carr, Bessie Smith and other musical luminaries, and the baseballers brought with them to the clubs and speakeasies a slew of local residents who had attended the game and wanted a chance to meet their hardball heroes.

That connection has been fairly well chronicled and illuminated by numerous researchers, in the fields of both historical research and artistic creation, and rightfully so. For example, Whitman College Professor of Music David Glenn married baseball and jazz in his critically acclaimed composition, “National Pastime.” And, as celebrated scholar, author, and music and baseball fan Gerald Early once famously said:

“There are only three things that America will be remembered for 2000 years from now when they study this civilization: The Constitution, jazz music and baseball. These are the three most beautiful things this culture’s ever created.”

There’s a reason that the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum and the American Jazz Museum are right across from each other in Kansas City’s legendary 18th and Vine District.

Gerald Early

But the music discussed so far is (or was) pretty much all urban jazz, blues and R&B, with big bands or swing blues combos or other formats facilitated by a populated region with ready access to the resources – manpower (and womanpower) and electricity and grand pianos and massive venues – necessary for that brand of soulful melodies.

What seems to have been somewhat overlooked, though, is any possible link between blackball and rural, country blues – which happens to be my favorite kind of blues. Almost the entirety of this genre is based in either the acoustic guitar, harmonica or a combination of the two, with progenitors and seminal figures like Patton, Hurt, Tommy Johnson, Robert Johnson, Son House, Blind Blake, Leadbelly, Memphis Minnie, Skip James, Blind Boy Fuller, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Willie McTell (yep, there’s a pattern there), and even Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf in their early days. There were also famed duos, like Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. (Instead of tediously giving links to each of these musicians named, I’ll direct you to Allmusic, a fantastic online database/encyclopedia/compendium of just about every musician who ever recorded. Just go to the homepage and type a name in search.)

These cats (and a few chicks) were often hoboes and itinerant ramblers, criss-crossing the rural South, which for decades was centered economically on massive plantations owned by rich white businessmen and populated by countless (often black) poor sharecroppers in what amounted to a 19th– and 20th-century feudal system. In fact, many of the legends of country blues were born and raised on plantations, and they bolstered their income by occasionally returning to the plantation system. The musicians played as many garden parties, juke joints and rent parties as they could to eke out something resembling a living.

But many Negro Leaguers also sprang from the rural Southern plantation system that birthed many a blues artist, one factor that might have bonded baseballers and musicians, at least in spirit. For example, fearless (often nasty) baserunner Crush Holloway, who was raised on a plantation in the Waco, Texas, area, told author John Holway for the latter’s book, “Voices from the Great Black Baseball Leagues”:

“I loved baseball. Out in them cotton fields I used to take a broomstick and took a whole pile of little rocks and hit. Imagination: That was a big deal. I’d hit a home run or a pop-up. Pop said, “If you don’t come in here, boy … out there in that dark.’ Just hitting those pebbles, you know? Imagination.

“Don’t tell me about working those cotton fields! My daddy had me out there early in the morning, getting them cows and things up. At sunrise we’d be in the field plowing. Oh that was big cotton – that was producing things down there then. Cotton and corn, wheat, all that stuff. …”

Likewise, baseball frequently became a focal point of plantation life, beginning with slave games on antebellum plantations and running through the employees and of ans sharecroppers on plantations who used the sport as exercise, recreation and entertainment, both for themselves and white audiences.

In fact, it was one of these situations from which came the earliest known film footage of African Americans playing baseball anywhere in the country – in 2014, University of Georgia researchers announced their discovery of such a film on the Pebble Hill Planation in Thomasville, Ga., dating to 1919.

The find caused a flurry of giddiness among scholars and enthusiasts of Negro and colored baseball who are constantly searching for such obscure gems. One of my SABR mentors, Dr. Leslie Heaphy, told the Thomasville (Ga.) Times-Enterprise:

“There is still so much of the story of black baseball to be found and examined for what it can tell us about baseball, African-American culture and American society. The footage from Pebble Hill shows us that we should not give up on finding other documents and materials that are still out there, waiting to be discovered.”

As is well known, the South at the time was blanketed by oppressive Jim Crow regimes, in which lynchings of African Americans happened almost weekly and the iron fist of segregation was rigidly enforced. Of course, Jim Crow thrived in Southern urban areas, but it was in “the country” and smaller towns where angry, violent mobs were allowed to storm local jail cells and where a boss on a levee construction crew could shoot an “insolent” Negro worker and have the body buried in the very levee the dead man helped to erect.

Bukka White

Meanwhile, in the socioeconomic reality of the early-20th-century rural South, countless amateur, club and semipro blackball teams emerged, some thriving for many years, many coming and going within the span of a single summer. While fully professional city teams like the Birmingham Black Barons, Atlanta Black Crackers, Memphis Red Sox, Nashville Elite Giants and New Orleans Black Pelicans existed over a span of decades, just about any small Southern hamlet with a significant African-American population scraped up a blackball team that composed of players and managers who frequently played for little more than a love for the game.

So, lately, this has been my question: Did any of these early country blues greats, especially those in the Mississippi Delta, play baseball on some level? Did they manage or even own teams? Or did they at least have some close connection to Negro hardball?

Those are questions I’m hoping to try to answer, or at least explore, over the next few months, with particular attention paid, at least initially, to two famed bluesmen – Bukka White and Robert Petway.

It looks like this post is nearly a year old, but I was wondering if you found anything. I am working on a project with my students using the blues to trace African American history. We will be reading Fences by August Wilson and was hoping to find a connection between blues music and baseball.

I was thinking country blues, but it could also be classic blues or early jazz.

LikeLike

Hi Charles, I’m so sorry it took me so long to respond! Thank you for reading and commenting. I do know that there’s a definite connection between the Negro Leagues and 1940s-era jump blues — Big Joe Turner, Louis Jordan and similar artists played at clubs frequented by Negro Leaguers and were often friends with them. There’s also been a fair amount written about the connection between jazz — especially early jazz (like Louis Armstrong, etc.) through swing (Duke Ellington, Count Basie, etc.) and early bebop. And course, Satchmo owned his own baseball team in New Orleans in the early 1930s! However, I haven’t been able to do further research on this subject, and I’ve been unable to find any solid proof of a connection between early country blues and black baseball. If you find anything, definitely let me know!

LikeLike

I’m glad you wrote this! As far as you know, are you the only person who’s written about these “plantation” baseball teams? I wrote about BB King and juke joint baseball teams for a Delta magazine:

http://www.bestofarkansassports.com/black-baseball-and-juke-joints/

LikeLike

Hi Evin, I’m so sorry it’s taken me this long to respond to your comment. Thank you for reading and commenting! Your article looks very intriguing — I’ll definitely take a close look at it. How much have you found about any possible black baseball teams in BB’s hometown of Indianola?

LikeLike

Pingback: B.B. King, Black Baseball and Juke Joints - Best of Arkansas Sports